|

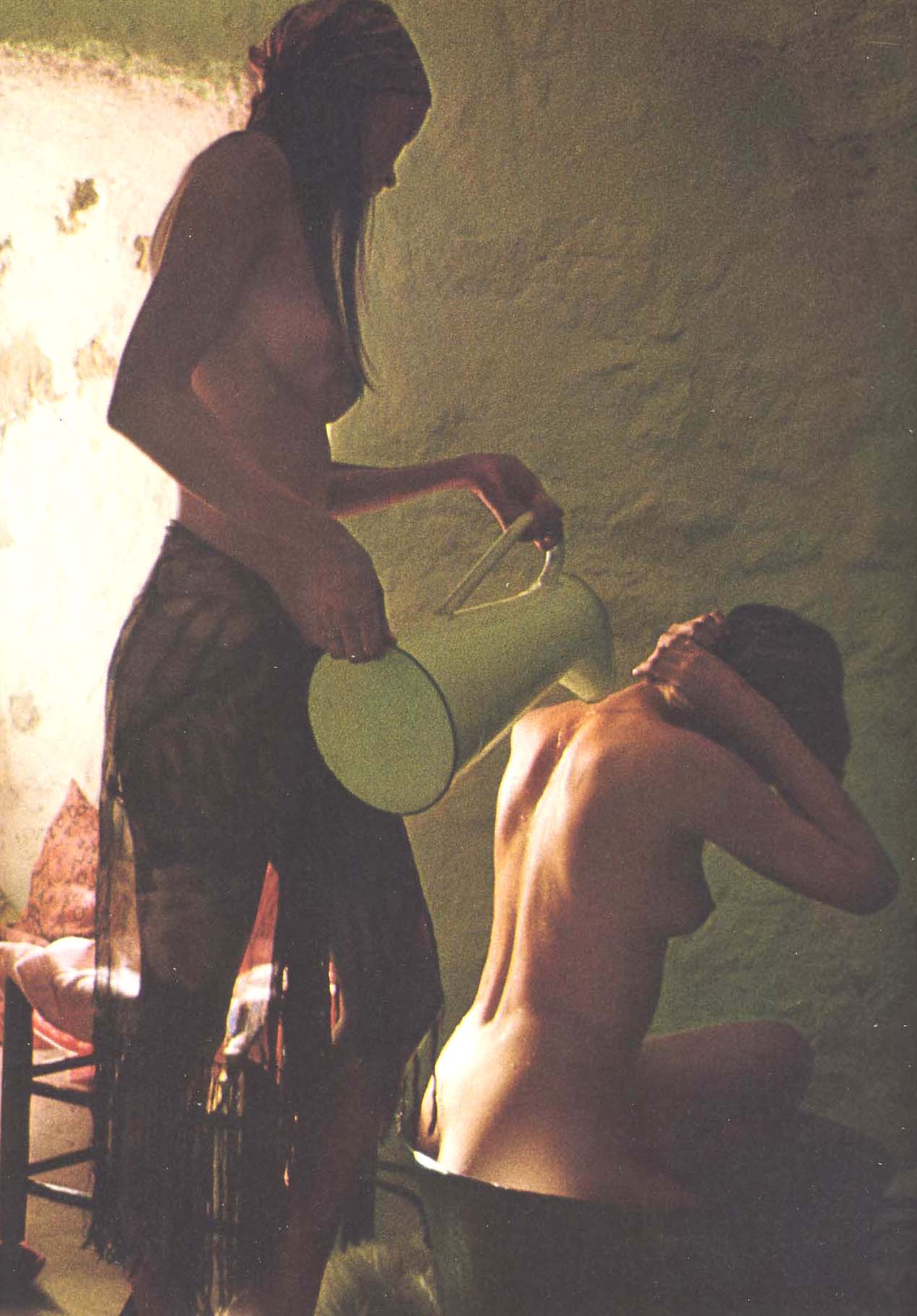

Three Photographers: David Hamilton, Jock Sturges and Sally Mann There are difficulties of determining artistic intention and even authorship in photography that do not pertain to painting or sculpture. One consequence is that the history or criticism of photography cannot with any confidence appropriate the terms of a painting-based history of style. The photographer’s style and even his vision are limited by technological decisions and givens of materiale that predate his undertaking any photographic project. For example, the limitations or opportunities of the film, the contrast, speed, color balance and grain all restrict stylistic choices on the part of a photographer (by restricting the number of his selection parameters) in a way that the support and the medium of painting do not. So do the image collecting properties of the lens (not just focal length but the very way the composite lenses are arranged to direct the light), available filtration and camera format. All this applies to film photography as it does mutatis mutandis to digital photography, the parameters of which are currently in constant flux because of the speed of technical innovation. In a way the blanche agonie does not exist for the photographer. Much of the surface is already filled in. The photographer can assert himself against these predetermined parameters by deliberate, often manual, intervention. But there is a frontier at which the resulting work is no longer a photograph but a composite that uses photographically derived means of applying color and line to a flat surface. There are two other less obvious limits to a photographer’s style. First, there is the sheer ease and speed with which an image can be created. The effect of this is that the competent photographer can assume a hundred different photographic and even painterly styles in as many days. He is less bound by the economic calculation of the effort and time required in creating a work, and so each individual work is less deliberate from a style standpoint. “Art” photographers tend to impose, artificially so to speak, the significance of these style decisions on themselves. But there is something essential in the very protean nature of the photographic medium. Moreover, in the case of figure photography and consequently nude photography, the model contributes as much to the final image as the photographer. Much can be done to change her appearance, but the presence of the model whose appearance is photographed is largely ineluctable. Once again, change her too much and she is no longer the model originally chosen. This is why in the passage from painting to photography, the identity and appearance of the model herself begins to supersede the technique, style or “world” of the photographer. Occasional models’ names come down to us from the classical world or the Renaissance, but only as afterthoughts, since it is known that she is only the starting point for the creation of the artist’s image. Models become more important in 19th century painting not simply because of the better reporting, but also because advances in technique and the turn to real time life studies led to images of recognizable individual women. Still there is a sudden and unbridgeable break in the transition from painting to photography. In photography the model is the co-creator of the image. Model searches are significant for the content of a photograph in a way they are not for painting. Finding the right model could be the most significant aesthetic act the photographer performs. The photographer can assert himself in his selection of models and in this case his actual control, as opposed to what happens with style decisions, is decidedly greater. Every photographer decides whom he will or will not shoot. However, the unavailability of the specific look he wants will limit his power of decision in a way that, in theory at least, the painter is not limited. David Hamilton did show us new things through his lens or showed them in a new way. Iconographically, he focused on adolescence and lesbianism. Stylistically he also moved his settings permanently out of the studio and the neutrality of seamless paper. His typical unarticulated background is identifiable as a wall and specifically the cool sort of plaster of the French Midi (most often shot with natural window light, minimum depth of field and varying degrees of graininess). He served up softness almost promiscuously achieving effects emotionally comparable to those produced by Guccione’s filtration around the same time. Comparisons of the two are interesting since together they were instrumental in showing alternatives to the prevailing style of nude photography. (Notably the critical differences come down to choice of model types, deliberate make-up effects with Guccione, none or almost none with Hamilton, Hamilton’s grain effects vs. Guccione’s filtration, the different settings and costumes chosen by both) Hamilton’s softening has the following effects: In color photography it limits the saturation, creating in one gesture a limited palette. It also serves to give the feeling of the past tense as if these photographs are memories. The sex happens not now but years ago and the image survives not as a record but as a vague memory image imprinted in the mind of the model, somewhat like a Freudian Deckerinnerung where, grown up, she remembers a moment of her life, but does so in a self-deceptive manner, from the outside, seeing herself through someone else’s eyes. (Hamilton claims he never used filters, which is not strictly true since a gauze curtain in front of a model is effectively a filter. And whether his effects were achieved in processing or in some other way during shooting, the result is much like some sorts of filtration.) Hamilton stands out because of his personal vision, which, when it appeared, was relatively new for the photographic nude: The sweet cusp of pubescence, the fleshy Eden of slim hips and large nipples sitting disproportionately on small breasts. The icon of the nude before Hamilton was Playboy’s big-boobed college girl, and , looking at a Hamilton, we felt as if we had never seen a nude before. I suppose one has to reach all the way back to Lucas Cranach, whom Hamilton acknowledges, to find something similar, something a world away from the ruler and compass dome hips of Renaissance and Baroque nudes. Equally Hamilton’s personal vision tends to idealize the image, casting the photographic nude as a non-specific female and avoiding thereby the excessive specificity of painters like Lequesne or Collier, whose very success in turning the nude into an individual person was often viewed as insufficiently aesthetic. Jock Sturges also shoots in the Midi but you do not feel the heat of the sun in his photos. The outlines are sharp and the air is cold, which gives them an air of unreality as if they were designedly museum objects. Despite their obsessive use of clear contours in tension with softly glowing light (Sturges shoots frequently in open sunlight which accounts for the hardness and sharpness of much of his imagery. Even his use of shade for modeling is rather high in contrast and so sharp around the edges. Mann takes advantage of the softer light of her environment with abundant use of cross shadows. The links in this essay are to high contrast jpegs that don't really represent the original silver gelatin prints at all well.), Sturges and Sally Mann display a hugely sentimentalized and possibly mendacious view of the family and the small community as the framework for the identity of the adolescents. The young nudes cannot be successfully defined outside of reference to their family or group. They do not exist outside that framework. These are indeed assertive neo-hippy families (Note how directly the characters stare at the viewer in most of the photos, as if they weren’t just nude; they also need to confirm their nudity). What is disturbing is that the family is one of the most favored institutions of despicable Xtian bourgeois society, and the embrace of the family by the fundamentally reactionary though confused counter culture movement shows a nostalgia barely distinguishable from that of your ordinary Sunday morning sermon. We cannot even see the adolescents divorced from their group, which subliminally gives them not only their identity but also whatever comfort and strength they may have (The favorite word in the textual commentaries is “connect”). But such a quasi-idyllic pastiche contains the lie of their art. For the family baptizes the emerging individual into unquestioning obedience, and parental oppression. It is the template for the universalized oppression we call a nation. It is a privileged or primal situation whose destruction is the work of a sort of metaphysically free act. The struggle to free oneself from the family and the shadeless treacle of this sort of imagery is waged in the expression of the adolescent’s sexuality - which is the same as her freedom. Is there a sense in which Mann represents a different view of the family from the oppressive tyrannical grouping that has been dubbed the bourgeois family but which in reality is the family, any family? Her Preface to Immediate Family contains indications along these lines. The world view behind her musings partakes of a happy communitarianism redolent of Woodstock and pantisocracies. I am rather inclined to think that these largely perceived (in Mann’s case perceived through the eye of memory) utopias really don’t address the central problem, which is the power structure inherent in the very notion of family. They have in the course of the past decades managed to impose on the rest of society an almost obsessive child worship. And indeed the only real consequence of that worship has been its cynical manipulation by goober preacherhood into a revival of sexual tyranny. It is noteworthy that Mann’s reminiscences are redolent with clichés lifted from Southern literary sources: the free thinking father (quite often a doctor), the miracle of nature seen through a child’s eyes, the strong armed elderly female (a relative? a slave? a former slave?), whose limbs may whither but whose spirit is dauntless. Hamilton’s women, in contrast, are family-free individuals, that is unbound by the oppressive imagery of “connecting.” They are context free as far as family or group is concerned, although, reminiscent of the naiads that more likely than not inspired much of Hamilton’s iconography, they merge into large tapestries of nature like elements in a frieze. Paradoxically their separateness is tied to integration with the woods and beaches from which they emerge fully developed, a delicate and yielding dragon seed. (The fractured groups – schools, families and the mysterious bande in Un Eté à St. Tropez - in Hamilton’s awkward films simply underline the feeling for the individual in his still photography.) Mann’s explicit identification with her subject matter makes her photos much more interactive, something very different from the uninvolved eye (There are exceptions, but the painter’s involvement in famous examples such as the Arnolfini Marriage Group or Las Meninas is part of the composition whereas Mann’s involvement is inextricably linked to the background iconography arising from our knowledge of the circumstances under which the photographs were made) of much Western art. The photographer is as much a part of the work of art as the individuals actually appearing in the images. Despite his lavish use of more obviously personally distinctive aestheticizing techniques, the eye of the Hamiltonian observer is much closer to that of Millet or Seurat - as close as he can possibly get to simply not being present. Sturges is somewhere between the two. He appears not to photograph his own family but acquaintances in communities he visits alone (though we need the commentary to realize this; nothing in the photographs themselves makes it obvious). He, like Mann, is somewhat of a figure in his photographs, but he is the essential outsider, whose participation is limited to observation and visual recording. Is the work of any of these photographers better than that of the others? The problem is we are loaded with culturally induced bad faith whenever we break into the realm of value judgment. (Have you ever noticed that practically the only thing οί πολλόι says or writes about art or “entertainment” is whether or not it pleases them? Comments that go further than thumbs up or thumbs down are notably missing from their phrase book.) For one thing, there is much room for doubt as to whether there is anything such as aesthetic quality at all, whether it isn’t just a scam, a fraudulent attempt to cover erotic feeling, which in the end is the only real source of pleasure in the visual arts. Likewise the discovery of aesthetic quality is invariably an introspective act and consequently not objective at all. Its communication to others may amount to a sort of anti-social imposition. One is tempted to say that the only thing that comes close to objectivity is the market. That is, the most aesthetically (or perhaps erotically) stimulating is in fact what sells best. Such a view approaches the truth only where the market is truly free. Otherwise, as we know, fanatic preachers are more than happy to manipulate market results to make it appear as if Disney kiddie porn had real value. |

Willis Domingo

There are naked women and big words inside. If you are under the age of 18, you do not belong here and should leave immediately by clicking here to exit. If you are an adult and do not wish to see erotic images of any kind or if you are simply stupid, click here to exit.